Archive

Supermoon Nonsense Redux: November 2016

There seems to be a growing excitement about the “Supermoon” that is due to occur on 14 November 2016, when the Moon will be at its closest to Earth in this orbit, and closer than it has been at any time since 1948.

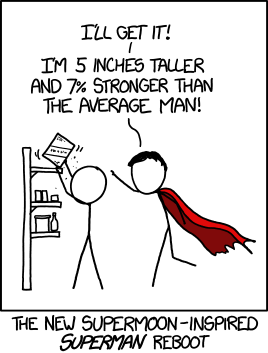

Sure the full moon will look big and bright this Sunday evening/Monday morning, but no more so than normal. It’ll be 14% larger and 30% brighter but your eyes and brain won’t see any difference from a normal full moon. It’s still worth a look – the moon is always a beautiful thing to see – but if you notice any difference in size or brightness, it’ll be your brain playing tricks on you. Maybe the power of suggestion or the Moon Illusion.

Read on to find out why it’s not any more super than normal…

The Moon orbits the Earth in an elliptical orbit, i.e. it is not perfectly circular, and so in each orbit there is a closest approach, called “perigee” and a furthest approach, called “apogee”.

At this month’s perigee the Moon will be 356,511km away from Earth. Closer than normal, sure but only 66km closer than the “Supermoon” that began all the hype back in 2011, so not that much closer.

Let’s start by comparing it to the Moon’s average distance from the Earth, which is ~385,000km. This perigee will be ~8% closer to the Earth than average. OK, that’s a bit closer, but not significantly so.

What about comparing it to the Moon’s average perigee distance, which is ~364,000km. So this “Supermoon” will be ~2% closer to the Earth than it is most months at perigee. Wow!

So what will this mean to you? Nothing at all. The Moon will be 14% bigger in the sky, but your eye won’t really be able to tell the difference. It will also be 30% percent brighter, but your eye will compensate for this too, so altogether this “Supermoon” will look exactly the same as it always does when it’s full.

As to all of those soothsayers claiming that there will be earthquakes and tidal waves. There very well might be, but they’ll be nothing at all to do with the Moon.

Post Script

Supermoons aren’t all that rare. In fact they occur once every 13.5 months.

Thanks to Steve Bell at the UK Hydrographic Office for providing the calculations below:

The Moon orbits the Earth once every 27.321 days (called the sidereal period), but as the Earth is orbiting the Sun at the same time, the Moon’s phases appear to repeat every 29.530 days (called the synodic period, which is the time we use to derive the month).

The Moon’s orbit is elliptical (a squashed circle) and so you would expect a perigee once every 27.321 days. However the elliptical path around which the Moon orbits the Earth precesses (that is it is not fixed with the perigee occurring at the same part of each orbit; the place where perigee occurs moves, or precesses) with a period of 8.8504 years, so that perigee doesn’t occur once every 27.321 days but rather once every 27.554 days (called the anomalistic period).

To calculate the frequency of perigee full moons (“Supermoons”) you need to use the equation:

1/P(perigee&full) = 1/P(perigee) – 1/P(full)

where P(perigee) is the anomalistic period = 27.554 days, and

where P(full) is the synodic period = 29.530 days

and when you put those figures in you find that a full moon will occur at perigee once every 411.776 days (i.e. P(perigee&full)=411.776), or just less than once per year.

British MP Wants Astrology To Play A Part In Health Policy

<rant>

Conservative MP David Tredinnick has recently spoken about his belief in astrology, and the fact that he thinks it should be integrated into UK health care.

It’s worth saying at the outset that astrology is bullshit.

The MP for Bosworth, Mr Tredinnick, is well known for his whacky beliefs, so much so that he is often referred to as the MP for Holland and Barrett, the high street purveyor of supplements, homeopathic remedies, and flim-flam.

What makes Mr Tredinnick’s comments so worrying is that he sits on the health committee and the science and technology committee in the House of Commons.

What makes this even more worrying is that these posts are elected by other MPs, so this believer in all things pseudo-science was deliberately placed on these committees by his fellow MPs.

It’s hard to imagine anyone less suited to judging the merits of health and science policy than a man who thinks that the stars and planets somehow influence our lives. This is a pre-scientific notion, and has no place in a modern society.

Mr Tredinnick has attempted to head off criticism from the reality-based community by referring to those rationalists and skeptics who disagree with his fanciful notions as “bullies” who had “never studied the subjects”.

On the contrary, most astronomers have studied the universe to a far deeper degree than most astrologers, and have come to the realisation that:

- there are no mechanisms by which the stars and planets can influence our lives

- one only needs conjure up a new mystical mechanism to account for astrology if there is significant evidence that it works

- there is no evidence that astrology works: none

</rant>

The Moon Illusion

You’ve probably all seen it before, a huge Full Moon sitting on the horizon. Time and again I have had people ask me why the Moon is so much bigger some times than others, and the answer is: it isn’t, really.

The Moon orbits the Earth in an elliptical orbit, meaning that it is not always the same distance from the Earth. The closest the Moon ever gets to Earth (called perigee) is 364,000km, and the furthest is ever gets (apogee) is around 406,000km (these figures vary a bit).

So the percentage difference in distance between the average perigee and the average apogee is ~10%. That is, if the Full Moon occurs at perigee it can be up to 10% closer (and therefore larger) than if it occurred at apogee.

This is quite a significant difference, and so it is worth pointing out that the Moon does appear to be different sizes at different times throughout the year.

But that’s NOT what causes the Moon to look huge on the horizon. Such a measly 10% difference in size cannot account for the fact that people describe the Moon as “huge” when they see it low on the horizon.

What’s really causing the Moon to look huge on such occasions is the circuitry in your brain. It’s an optical illusion, so well known that it has its own name: the Moon Illusion.

If you measure the angular size of the Full Moon in the sky it varies between 36 arc minutes (0.6 degrees) at perigee, and 30 arc minutes (0.5 degrees) at apogee, but this difference will occur within a number of lunar orbits (months), not over the course of the night as the Moon rises. In fact if you measure the angular size of the Full Moon just after it rises, when it’s near the horizon, and then again hours later once it’s high in the sky, these two numbers are identical: it doesn’t change size at all.

So why does your brain think it has? There’s no clear consensus on this, but the two most reasonable explanations are as follows:

1. When the Moon is low on the horizon there are lots of objects (hills, houses, trees etc) against which you can compare its size. When it’s high in the sky it’s there in isolation. This might create something akin to the Ebbinghaus Illusion, where identically sized objects appear to be different sizes when placed in different surroundings.

2. When seen against nearer foreground objects which we know to be far away from us, our brain thinks something like this: “wow, that Moon is even further than those trees, and they’re really far away. And despite how far away it is, it still looks pretty big. That must mean the Moon is huge!”.

These two factors combine to fool our brains into “seeing” a larger Moon when it’s near the horizon compared with when its overhead, even when our eyes – and our instruments – see it as exactly the same size.

Supermoon Nonsense

There seems to be a growing excitement about the “Supermoon” that is due to occur on 19 March 2011, when the Moon will be at its closest to Earth in this orbit, and closer than it has been at any time since 1992.

The Moon orbits the Earth in an elliptical orbit, i.e. it is not perfectly circular, and so in each orbit there is a closest approach, called “perigee” and a furthest approach, called “apogee”.

At this month’s perigee the Moon will be 356,577km away from Earth, and will indeed be at its closest in almost 20 years [This is WRONG: see Update 2 below!). But how close is it compared with other perigees?

Let’s start by comparing it to the Moon’s average distance from the Earth, which is ~385,000km. This perigee will be ~8% closer to the Earth than average. OK, that’s a bit closer, but not significantly so.

What about comparing it to the Moon’s average perigee distance, which is ~364,000km. So this “Supermoon” will be ~2% closer to the Earth than it is most months at perigee. Wow!

So what will this mean to you? Nothing at all. The Moon will be a few percent bigger in the sky, but your eye won’t really be able to tell the difference. It will also be a few percent brighter, but your eye will compensate for this too, so altogether this “Supermoon” will look exactly the same as it always does when it’s full.

As to all of those soothsayers claiming that there will be earthquakes and tidal waves. There very well might be, but they’ll be nothing at all to do with the Moon.

UPDATE: I predict that lots of people will report having seen a huge Moon on or around 19 March

UPDATE 2: Thanks to “justcurious” for the comment that inspired this calculation, and to Steve Bell at the UK Hydrographic Office for providing the calculations below:

The Moon orbits the Earth once every 27.321 days (called the sidereal period), but as the Earth is orbiting the Sun at the same time, the Moon’s phases appear to repeat every 29.530 days (called the synodic period, which is the time we use to derive the month).

So the first part of the answer is: the Moon is full every 29.530 days.

The Moon’s orbit is elliptical (a squashed circle) and so you would expect a perigee once every 27.321 days. However the elliptical path around which the Moon orbits the Earth precesses (that is it is not fixed with the perigee occuring at the same part of each orbit; the place where perigee occurs moves, or pressesses) with a period of 8.8504 years, so that perigee doesn’t occur once every 27.321 days but rather once every 27.554 days (called the anomalistic period).

To calculate the frequency of perigee full Moons you need to use the equation:

1/P(perigee&full) = 1/P(perigee) – 1/P(full)

where P(perigee) is the anomalistic period = 27.554 days, and

where P(full) is the synodic period = 29.530 days

and when you put those figures in you find that a full Moon will occur at perigee once every 411.776 days (i.e. P(perigee&full)=411.776, or just less than once per year.

All the articles that cite this as the closest full Moon in 18.6 years are wrong; there was a full Moon at perigee 411.784 days ago, on Feb 28th 2010 when the full Moon occurred at 1700UT and perigee occurred just 19 hours before at 2200UT on Feb 27th 2010.

The next so-called Supermoon will occur on May 6th 2012, when the full Moon will occur at 0400UT, with perigee at the same time.

The Circle of Little Animals

This is an auspicious time of the year.

The Sun, on its yearly circuit of the sky*, moves gradually along the ecliptic, a line which is the projection of our solar system’s disk onto our night sky. This line, the ecliptic, is also known as the zodiac, a term originating from the late 14th Century, and deriving from the Greek literally translating as “circle of little animals”. (Incidentally our word for zoo derives from the same origin).

To the ancient Greeks this was indeed a circle of little animals, featuring: a ram, Ares; a bull, Taurus; Pisces the Fish; and many other well known (for all the wrong reasons) constellations. It also features three humans: Aquarius the Water Carrier, said to represent Ganymede, beloved of Zeus; and Gemini the Twins, Castor and Pollux.

The only zodiac constellation which is inanimate is Libra the Scales, taken from Babylonian astrology. The Greeks however didn’t recognise Libra; instead they thought that the stars here marked out Scorpius’ claws, which they considered to be a separate sign.

So the twelve constellations that lie along the ecliptic are most well-known due to astrology, a pseudo-science that suggests there is some significance to which constellation the Sun was in when you were born. This is, of course, bullshit.

There are so many reasons why astrology should be laughed off as pre-scientific magical thinking (no evidence, no mechanism by which it might work, inconsistent etc) but next time you meet an astrologer ask them what star sign you would be if you were born between 30 November and 18 December. If they tell you Sagittarius (if they’re a Hindu astrologer they might also say Scorpius) then tell them they are plain wrong.

On these 18.4 days of the year the Sun is wonderfully absent from the usual twelve zodiac signs, It is still there, however, gracefully moving along the ecliptic, but between 30 November and 18 December it is in the constellation of Ophiuchus the Serpent-bearer.

Ophiuchus does not appear in any astrologer’s zodiac. Back in the early days of astrology, when it was first dreamed up several thousand years ago, there were indeed only twelve constellations lying along the zodiac. Over the past few millennia however the Earth’s axis has wobbled slightly (an effect called precession) with the result that the line of the ecliptic has moved with respect to the constellations, and so an interloper, Ophiuchus, has crept in.

So celebrate all those of you born between 30 November and 18 December (one person in twenty share this star sign); you’re not a Sagittarian at all; you’re an Ophiuchan.

It’s still all bullshit though.

* the Sun, of course, does not orbit the Earth, it’s the other way around. It just looks like it does from down here…