Archive

2015: The Year of Dwarf Planets and Small Solar System Bodies

We’re currently living through a very exciting time in space exploration, with a small armada of robot space probes visiting previously unexplored corners of our solar system. Here’s just a few of the amazing discoveries we’ve made in the past few weeks.

This year sees us make close encounters with two of the largest dwarf planets, as New Horizons flies past Pluto for the first time, and Dawn continues to orbit the giant asteroid Ceres. All this as the Philae Lander continues to try to make contact with us from the surface of Comet 67P/Churyumov-Gerasimenko as its parent spacecraft Rosetta follows the comet around the Sun.

Each of these missions is very exciting in its own right, but to have all three happening at once is incredible.

Rosetta and Philae Latest

The Rosetta Orbiter arrived at Comet 67P/Churyumov-Gerasimenko in August last year, and the Philae lander descended onto the comet’s surface in November, carrying out its science mission for 60 hours before its batteries died. Rosetta has continued to produce great science since then; its latest scoop was the discovery of what appear to be sink-holes on the comet’s surface.

All this while Philae tries to make contact with us, and Comet 67P begins the outgassing that will eventually form its tail as the comet makes its closest approach to the Sun on 12 August 2015.

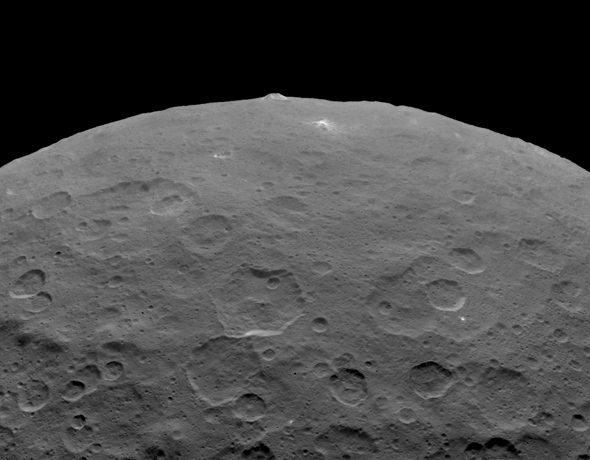

Dawn Latest

The Dawn spacecraft arrived at Ceres in March 2015, after having spent over a year orbiting the smaller asteroid Vesta. Ceres is the largest of the asteroids, so large in fact that it’s considered a dwarf planet, its gravity having pulled it into a spherical shape.

More and more mysteries are arising as a result of Dawn’s asteroid mission including: what are these bright patches inside craters on Ceres’ surface?

and: what’s a mountain doing on an asteroid?

New Horizons Latest

Stay tuned for even better images of Pluto as New Horizons speeds towards its 14 July flyby at close to 60000kph. For now the best images we have of Pluto and its moon Charon are from New Horizons’ Long-Range Reconnaissance Imager, which shows features on the surface of the distant Dwarf Planet, which we’ll see in better detail in the next couple of weeks.

Other Missions

This is on top of all of the other missions going on up in space right now: Cassini continues to send back breath-taking images and data from the ringed planet Saturn and its moons; no fewer than five spacecraft are currently in orbit around Mars – NASA’s 2001 Mars Odyssey, , Mars Reconnaissance Orbiter, and MAVEN, ESA’s Mars Express, and India’s Mangalyaan – while two intrepid rovers – Opportunity and Curiosity – explore Mars’ surface; and our own Moon is orbited by the Lunar Reconnaissance Orbiter.

We’ll add to this over the next few years, as the Juno probe reaches Jupiter in summer 2016, and as the Japanese mission Hayabusa 2 enters into orbit around an asteroid in 2018 and returns a sample to Earth on 2020.

Watch a Star Disappear Behind an Asteroid: Wednesday 10 September 2014

Many thanks to the always-excellent Astronomy Now magazine for this story. Their full article is here, and is well worth a read.

In the early hours of the morning of Wednesday 10 September (at around 0306BST) stargazers in the northern part of the British Isles have the chance to witness a star disappearing, if only for a few seconds.

The star in question – HIP 22792 in the constellation of Taurus – is faint, though, and so you won’t see it with your naked eye. The good news is that you can see it through even a modest pair of binoculars mounted on a tripod, and it’s easily seen through a telescope.

So why is it blinking off and on again? In fact it isn’t, but for those few seconds a much smaller but much closer object, an asteroid called (569) Misa will pass in front of it, perfectly obscuring it for observers in a 90km wide band running from Galway in Ireland all the way up to Peterhead near Aberdeen. Observers within this band will see the occultation, and those near the centre line (including me in Glasgow and stargazers in Sligo, Londonderry, and Dundee) will get the best view, with the occultation lasting longest (3.6 seconds!).

How to find HIP 22792

The faint star in question is located in the constellation of Taurus, and will be around 38° above the eastern horizon at the time of occultation. Luckily there are plenty of bright stars nearby to signpost you there.

Here’s a close up of the area in question:

The stars labelled in red (by me) are the signposts to HIP 22792. Stars a and b (ι Tau and τ Tau) are both naked eye in anything other than bright city light pollution, shining at magnitudes +4.6 and +4.3 respectively. This makes them very easy to spot in binoculars. Draw an imaginary line between a and b and cut it with a perpendicular line moving in the opposite direction from the bright star of Aldebaran, and the next bright-ish star you come to is labelled c, HIP 22743, which shines at +6.5. Continue along this line past a faint star (unlabelled) shining at +7.4, then double that distance again to find the target, HIP 22792, which is the faintest so far, at +7.6. The stars labelled d and e are there for reference, and are at +5.8 and +6.3 respectively.

Practical tips for finding HIP 22792

If you have a telescope with in-built goto and tracking you’re good to go but for the rest of us we need to do a bit of prep.

- At the very least you’ll need to mount your binoculars on a steady tripod, or have your scope aligned, so that you can track the target for several minutes.

- Finding it may take some time so don’t just fall out of bed expecting to locate it easily. Give yourself at least 20 minutes of set-up (or more, if you’re new to this!)

- Make sure you’re observing from a site that has a good eastern view, that isn’t obscured by buildings or trees

- As always, the further you can get from the glare of street lights the better.

August Asteroids: 3 Juno and 7 Iris at Opposition

This month two of the brightest asteroids, 3 Juno and 7 Iris, will be at opposition in our skies, giving a great opportunity for asteroid hunters to track down these lumps of space rock.

Bear in mind though that you (almost certainly) won’t be able to see them with the naked eye, and that you’ll need binoculars on a tripod or a telescope to find them properly. And even then they’ll just look like very faint stars. But they’re not stars; they’re asteroids, lumps of rock in our solar system orbiting the Sun between Mars and Jupiter.

How big and bright are they?

3 Juno and 7 Iris are amongst the largest of the asteroids, a few hundred kilometres along any one axis. This might seem pretty big but they’re tiny compared to the planets, and so don’t reflect nearly as much light back to us, and are therefore much fainter.

Their magnitudes vary depending on how far away they are from us. They both vary between around seventh and eleventh mag; at their brightest 3 Juno is magnitude 7.4 and 7 Iris is magnitude 6.7. This only occurs under perfect conditions, and this year’s oppositions for both asteroids won’t have them presenting their very brightest aspect. The generally-accepted view is that the human eye can only see down to magnitude 6, but in exceptional circumstances – very dark skies free from light pollution, and very good atmospheric conditions – and with exceptional eyesight, you might just be able to see 7 Iris when it’s closest to us, and at its brightest.

When can I see them?

They’re visible all month but the best time to look at them is when they’re at opposition. That means they’re directly opposite the Sun in the sky, and therefore rise as the Sun sets and set as the Sun rises, getting to their highest due south around midnight.

3 Juno reaches opposition on Sunday 4 August 2013 and it’ll brighten up to magnitude 9. You’ll need a scope, a good star map, and patience to track it down.

7 Iris reaches opposition on Friday 16 August 2013, and it’ll be brighter than 3 Juno, but still not near its best, gaining magnitude 8 during this year’s opposition. Again, a good star chart and telescope is needed.

Where can I see them?

They are both visible in the lower part of the southern sky in the constellation of Aquarius, but you’ll need very detailed star maps to help you find them. 7 Iris is only a degree or so away from the brightest star in Aquarius, β Aquarii, on the night of opposition, making it a bit easier to find. The British Astronomical Association computing section has downloadable star-charts to help you find these asteroids, and others.

How will I know that I’m looking at an asteroid?

The short answer is: you won’t, at least not at first. Asteroids, even the brighter ones like 3 Juno and 7 Iris, will only ever appear as tiny specks of light when seen through a telescope, just like the millions of other tiny specks of light, the stars. However if you observe them over the course of a number of nights around opposition, and mark their position on a star map, then you’ll notice that their position changes relative to the “fixed” stars, as they circle the Sun and move through space.

Don’t be put off if you don’t manage to find them. While you’re out hunting for them don’t forget you can check out lots of other amazing sights through your telescope. Why not have a go at finding the Ring Nebula in Lyra, high overhead this month.

Good luck, and happy asteroid-hunting!

Russian Meteor 15/02/13

News reports have recently come in of a huge meteor exploding in the air over the Russian cities of Yekatarinburg and Chelyabinsk (about 200km apart), injuring hundreds of people. It’s worth clarifying some of the facts in this matter:

The object that exploded was a meteor, a lump of space rock passing through the Earth’s atmosphere. In this particular case the meteor appears to have exploded around 10km above the ground, over the city of Chelyabinsk.

The shockwave from the explosion damaged some buildings, shattered windows, and set off car alarms. It appears that most of the injuries came from the broken glass, not from the meteor itself hitting anyone.

Showers of fragments from the meteor have been reported too, falling after the explosion over a large area of Russia.

The meteor poses no risk to us any more; it’s all burned up, and it was a one-off random event. Such things are not that rare, happening once every few years, but this one just happened to fall over a populated area.

This meteor was unrelated to asteroid 2012 DA14 that is due to pass by the Earth later today.

UPDATE: A 6m diameter crater has been found in the ice & snow of Lake Chebarkul where the meteorite is thought to have landed:

Close Encounters with Asteroid 2005 YU55

This evening (8 November 2011) at 2328 GMT a 400m diameter asteroid will hurtle past the Earth, missing us by an astronomical whisker, less than 200,000 miles. The chunk of space debris in question is snappily titled 2005 YU55.

Radar image of 2005 YU55 taken at 1945UT on 7 November 2011, when the asteroid was 1.38 million km away

This kind of asteroid fly-by is rather rare. The last time that something this size passed so close to us was in 1976, and the next time it’s due to happen (that we know of) is 2028. Still, tonight’s pass poses absolutely no risk to the Earth.

Asteroid 2005 YU55 was discovered, as its name suggests, is 2005. This designation method is used by the Minor Planet Center, and designates minor planets until a proper name is given (if ever). Upon discovery it became clear that this asteroid was one of the Apollo asteroids, near-Earth asteroids named after 1862 Apollo, the first of the group to be discovered. The Apollo asteroids are all Earth-crossing asteroids, and so warrant special attention. The fact that their orbits cross that of the Earth does not automatically mean they pose a threat of impact, but does mean that we need to very carefully monitor their orbits in case they are on a collision course with us in the future.

Astronomers rank near-Earth asteroids relative to the risk they pose to us using the Torino Impact Hazard Scale. This ten point scale runs from 0, meaning that “the likelihood of a collision is zero, or is so low as to be effectively zero”, to 10, meaning “a collision is certain, capable of causing global climatic catastrophe that may threaten the future of civilization as we know it”. 2005 YU55 is currently ranked at 0 in this scale. There are no asteroids currently known that are ranked higher than 1. The highest ranking ever given was 4, given briefly to asteroid Apophis, meaning “a close encounter, meriting attention by astronomers…[with] a 1% or greater chance of collision capable of regional devastation”, but this has since been downgraded to a 0 based on new observations refining its orbit.

Asteroid 2005 YU55 will not be visible to the naked eye, but amateur astronomers with good telescopes, and knowledge of how to use them, might locate it. See Robin Scagell’s excellent description of how to find it over at the Society for Popular Astronomy.

If 2005 YU55 did hit the Earth (it won’t) it could certainly destroy a large city and cause significant loss of life (to find out what would happen head over to the Down 2 Earth Impact Simulator) which is just one of the reasons that asteroid observation projects are so important.