Archive

Autumn Equinox 2014

Today, 23 September 2014, marks the moment of the Autumn Equinox. At 0229 UT (0329 BST) the Sun will cross from the northern hemisphere sky to the southern, and we’ll begin the slow approach to the Winter Solstice on 21 December.

The equinoxes (one in spring and one in autumn) are the two instances every year when the Sun makes that crossing from north to south and vice versa, and they’re commonly thought to be the days when day and night are equal length, but they’re really not, for reasons I’ve outline before:

- Astronomers measure the timings of equinoxes, sunrises and sunsets based on the middle point of the Sun’s disk in the sky, so when you read a sunrise time it means the time that the centre of the Sun’s disk rises above the horizon. For a few minutes before that time the top of the Sun’s disk will already have risen, giving “daylight”.

- Even before this happens the sky is lit up by the Sun below the horizon, and we experience twilight. Most people would think that the sky is bright enough to call it “daytime” long before the Sun pops above the horizon, during the phase of civil twilight.

- So today, even though day and night are said to be equal on the equinox, the “daytime” (i.e the start of civil twilight) started about 0625BST in Glasgow (where I am) and will end this evening around 1950BST, giving me approx. 13.5 hours of “daylight”. (Londoners will have from about 0615 until 1930BST, or approx. 13.25 hours of “daylight”).

The day this year where I have exactly 12 hours of “daylight” (i.e. between the morning start and the evening end of civil twilight) is 11 October and this day is called the equilux. (In London the equilux falls on 12 October).

Autumn Equinox 2013

Today, 22 September 2012, marks the moment of the Autumn Equinox. At 2044 UT (2144 BST) the Sun will cross from the northern hemisphere sky to the southern, and we’ll begin the slow approach to the Winter Solstice on 21 December.

The equinoxes (one in spring and one in autumn) are the two instances every year when the Sun makes that crossing from north to south and vice versa, and they’re commonly thought to be the days when day and night are equal length, but they’re really not, for reasons I’ve outline before:

- astronomers measure the timings of equinoxes, sunrises and sunsets based on the middle point of the Sun’s disk in the sky, so when you read a sunrise time it means the time that the centre of the Sun’s disk rises above the horizon. For a few minutes before that time the top of the Sun’s disk will already have risen, giving “daylight”.

- Even before this happens the sky is lit up by the Sun below the horizon, and we experience twilight. Most people would think that the sky is bright enough to call it “daytime” long before the Sun pops above the horizon, during the phase of civil twilight.

So today, even though day and night are said to be equal on the equinox, the “daytime” (i.e the start of civil twilight) started about 0630BST in Glasgow (where I am) and will end this evening around 2000BST, giving me 13.5 hours of “daylight”. (Londoners will have from about 0615 until 1930BST, or approx. 13.25 hours of “daylight”).

The day this year where I have exactly 12 hours of “daylight” (i.e. between the morning start and the evening end of civil twilight) is 11 October and this day is called the equilux. (In London the equilux falls on 12 October).

Autumn Equinox 2012

Today, 22 September 2012, marks the moment of the Autumn Equinox. At 1449 UT (1549 BST) the Sun will cross from the northern hemisphere sky to the southern, and we’ll begin the slow approach to the Winter Solstice on 21 December.

The equinoxes (one in spring and one in autumn) are the two instances every year when the Sun makes that crossing from north to south and vice versa, and they’re commonly thought to be the days when day and night are equal length, but they’re really not, for reasons I’ve outline before:

- astronomers measure the timings of equinoxes, sunrises and sunsets based on the middle point of the Sun’s disk in the sky, so when you read a sunrise time it means the time that the centre of the Sun’s disk rises above the horizon. For a few minutes before that time the top of the Sun’s disk will already have risen, giving “daylight”.

- Even before this happens the sky is lit up by the Sun below the horizon, and we experience twilight. Most people would think that the sky is bright enough to call it “daytime” long before the Sun pops above the horizon, during the phase of civil twilight.

So today, even though day and night are said to be equal on the equinox, the “daytime” (i.e the start of civil twilight) started about 0630BST in Glasgow (where I am) and will end this evening around 2000BST, giving me 13.5 hours of “daylight”. (Londoners will have from about 0615 until 1930BST, or approx. 13.25 hours of “daylight”).

The day this year where I have exactly 12 hours of “daylight” (i.e. between the morning start and the evening end of civil twilight) is 11 October and this day is called the equilux. (In London the equilux falls on 12 October).

Equinox, Equilux, and Twilight Times

On or around 21 March each year it is the Spring Equinox in the Northern Hemisphere, the day when eggs can be stood on their ends, when the Sun crosses the celestial equator, and when night and day are equal length the world over.

But this last part isn’t entirely true, for a variety of reasons.

Equinox

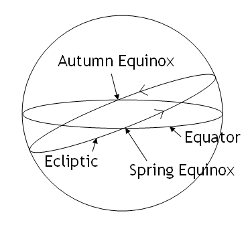

Equinox is latin for aequus (equal) and nox (night) meaning, roughly, “equal night”. The moment of the equinox is defined as the point at which the centre of the Sun’s disk crosses an imaginary line in the sky called the celestial equator, the projection of the Earth’s equator out into space.

The Sun (and the Moon and all the planets) move along a line in the sky called the ecliptic, the projection of the disk of the solar system out into space. These two lines, the equator and the ecliptic, cirlce the sky, and because the Earth’s axis is tilted at 23.5 degrees the angle between the equator and the ecliptic is 23.5 degrees, and the two circles meet at only two points, called equinoctial points.

Over the course of the year the Sun, as seen from Earth, appears to make one complete circuit around the ecliptic, as the Earth in fact orbits the Sun. And so on two days each year the Sun’s path crosses the equator. This means a number of things:

1. that an observer at the equator will see the Sun directly overhead at mid-day on the equinoxes

2. that the Sun will rise due east and set due west on the equinoxes (on all other days the Sun will rise either north or south of east, and set north or south of west)

3. the length of day and night are nearly equal

On this last point, they are not exactly equal, for two reasons:

1. the Sun appears as a disk in the sky with a radius of around 16 arcminutes, and so the top of the Sun appears to rise while the centre of the disk is still below the horizon, and the instant of the equinox is measured with respect to the Sun’s centre, and

2. the Sun’s light is bent, or refracted, in the Earth’s atmosphere, so that rays from the Sun can light you up even before the Sun rises, and keep you lit after it sets, with the degree of refaction being around 34 arcminutes

These two factors combine to mean that the Sun will appear to have “risen” when the centre of the disk is still 50 arcminutes (16 + 34) below the horizon, making the amount of daylight longer than the expected 12 hours. How much longer depends on where on Earth you are, but in the UK the length of the day is approx. 12 hours 10 minutes, rather than exactly 12 hours.

Equilux

Because of this effect, the days on which the length of day and night are exactly equal, called the equilux, occur a few days before the spring equinox and a few days after the autumn equinox. This date will vary depending on where on Earth you are, and indeed equiluxes do not occur at all close to the equator, whereas the equinox is a fixed instant in time.

Twilight

But the story doesn’t end there. Even on the days of equilux, the sky will have been bright for some time before the first rays of the Sun hit you, and will remain bright for some time after the last rays disappear from view. This time of day is called twilight, starting at dawn and ending at dusk.

There are, in fact, three kinds of twilight.

Civil twilight is what most people mean when they talk about twilight. It starts in the morning when the centre of the Sun’s disk is 6 degrees below the horizon, and ends at sunrise. In the evening civil twilight stars at sunset and continues until the centre of the Sun’s disk is 6 degrees below the horizon. During civil twilights the sky is still bright enough that, in general, artificial illumination will not be needed when doing things outside. In reality though, most councils switch lights on a fixed time after sunset (say 30 minutes) and turn them off a fixed time before sunrise, rather than relying on the Sun’s angular distance below the horizon.

Nautical twilight is when the Sun’s disk is between 6 and 12 degrees below the horizon. During nautical twilight it is still possible to distinguish the sky from the distant horizon when at sea, thus allowing sailors to take measurements of bright stars against the horizon. Most of us would consider this “dark”, but it is still technicaly twilight.

Astronomical twilight is when the Sun’s disk is between 12 and 18 degrees below the horizon. During astromical twilight you’ll no longer be able to tell the sky from the distant horizon when at sea, but crucially for astronomers, there is still light in the sky. Not much – indeed most of us would say it’s properly night time at this point – but the faintest objects in the sky, such as nebulae and very dim stars, will only be visible after astronomical twilight ends. Also, if you intend to measure how dark the sky is using a Sky Quality Metre, say, it is important to wait till after astronomical twilight.

So how much daytime does this twilight add? Only during civil twilight can the sky really be considered “light”, and so we can say that the day begins (at the point we would call dawn) at the start of morning civil twilight, and ends, (at the point we would call dusk) at the end of evening civil twilight. This means that on the Spring Equinox, the “day” will be around 13 hours and 15 minutes long in the UK (depending on where you are).

The date at which the “day” (including dawn and dusk) is 12 hours long in the UK (and therefore when we had equal amounts of daytime and nighttime) occurs around 01 or 02 March, over two weeks before the so-called equinox!

To find out your local sunrise / sunset / twilight times visit www.timeanddate.com