Archive

Constellation of the Month: Hercules

The month of June has the shortest nights of the year (for northern hemisphere stargazers), but there’s still plenty to see if you wait till the sky gets dark after midnight.

Sitting high in the south – almost directly overhead – during June is the constellation of Hercules.

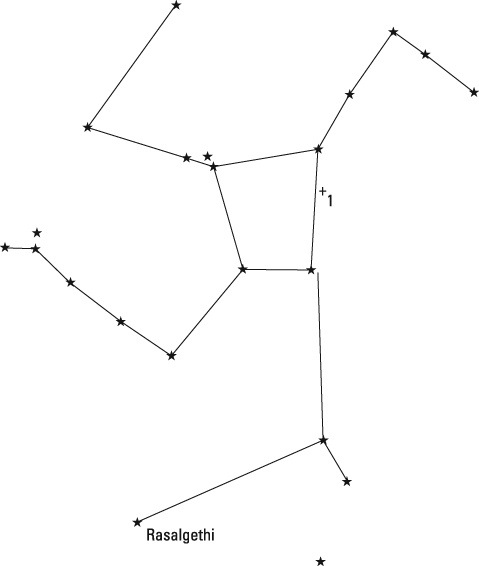

The body of Hercules is made up of four stars in an asterism known as The Keystone. The four stars in The Keystone, like all the star in Hercules, are not especially bright, so the pattern doesn’t stand out all that clearly. To find it draw a line from the bright orange star Arcturus to the bright white star Vega. Hercules sits about 2/3 of the way along this line.

Once you find the Keystone try and trace the four lines that come off each corner, Hercules’s arms and legs.

But the most interesting feature in Hercules is the faint fuzzy patch known as the Great Globular Cluster in Hercules, M13 (marked with a + above).

M13 lies on a line drawn between two of the stars of the Keystone, ζ and η Her. It’s just visible to the naked eye in dark sky conditions (which you won’t get during the summer months) but is easily found using binoculars. It will look like a fuzzy out-of-focus star.

In fact it is a globular (globe-shape) cluster of around 300,000 very old stars, orbiting our galaxy.

If you’ve got a powerful telescope then you should be able to make out individual stars within this cluster.

Summer Solstice 2012

The northern hemisphere summer solstice occurs today, 20 June 2012 at 2309 UT (which is actually tomorrow in the UK, 21 June 2012 at 0009 BST).

But surely the summer solstice is just the longest day. How can it “occur” at a specific instant?

That’s because we astronomers define the summer solstice as the instant when the Sun gets to its furthest north above the celestial equator. Or to put it another way, the instant when the north pole of the Earth is tilted towards the Sun as far as it can.

And this happens at exactly 2309 UT on 20 June 2012.

It’s important to remember though that while we are in the midst of summer, the southern hemisphere are experiencing their winter solstice, and their shortest day.

And how much longer is our “longest day”? In Glasgow, my home town, the Sun will be above the horizon for 17h35m13s today and tomorrow (20 and 21 June), a full seven seconds longer than yesterday, and eight seconds longer than 22 June.

The Lowest Full Moon of the Year

Tonight (actually around 0130 tomorrow morning) the Full Moon will reach its highest point due south, just an hour and a half after the eclipse ends. Despite being at its highest in the sky, you’ll still struggle to see it, as it is very low down. In fact the Full Moon nearest the Summer Solstice is the lowest Full Moon of the Year.

Full Moon by Luc Viatour http://www.lucnix.be

First, let’s begin with the definition of “Full Moon”. A Full Moon occurs when the Moon is diametrically opposite the Sun, as seen from the Earth. In this configuration, the entire lit hemisphere of the Moon’s surface is visible from Earth, which is what makes it “Full”. There is an actual instant of the exactly Full Moon, that is the exact instant that the Moon is directly opposite the Sun. Therefore when you see timings listed for the Full Moon they will usually include the exact time (hh:mm) that the Moon is 180° round from the Sun (we call this point opposition).

Here’s a list of the times of all Full Moons between June 2011 and June 2012:

| Month | Date of Full Moon |

Time of Full Moon (UT) |

| June 2011 | 15 June | 2014* |

| July 2011 | 15 July | 0640* |

| August 2011 | 13 August | 1857* |

| September 2011 | 12 September | 0927* |

| October 2011 | 12 October | 0206* |

| November 2011 | 10 November | 2016 |

| December 2011 | 10 December | 1436 |

| January 2012 | 09 January | 0730 |

| February 2012 | 07 February | 2154 |

| March 2012 | 08 March | 0939 |

| April 2012 | 06 April | 1919* |

| May 2012 | 06 May | 0335* |

| June 2012 | 04 June | 1112* |

* UK observers should add on one hour for BST

As you can see from this table, the instant of the Full Moon can occur at any time of day, even in the daytime when the Moon is below the horizon. So most often when we see a “Full Moon” in the sky it is not exactly full, it is a little bit less than full, being a few hours ahead or behind the instant of the Full Moon. I’ll refer to this with “” marks, to distinguish this from the instant of the Full Moon (they look virtually identical in the sky).

The Moon rises and sets, like the Sun does, rising towards the east and setting towards the west, reaching its highest point due south around midnight (although not exactly at midnight, just like the Sun does not usually reach its highest point exactly at noon). And like with the Sun the maximum distance above the horizon of the “Full Moon” varies over the year.

The Sun is at its highest due south around noon on the Summer Solstice (20 or 21 June) and at its lowest due south around noon on the Winter Solstice (21 or 22 Dec) (of course the Sun is often lower than this, as it rises and sets, but we’re talking here about the lowest high point at mid-day, i.e. the day of the year in which, when the Sun is at its highest point that day, that height is lowest…)

And because Full Moons occur when the Moon is directly opposite the Sun, you can imagine the Moon and Sun as sitting on either sides of a celestial see-saw: on the day when the Sun is highest in the middle of the day (in Summer), the Moon is at its lowest high point at midnight; and on the day when the Sun is at its lowest high point in the middle of the day (in Winter), the Moon is at its highest high point at midnight.

This means, in practical terms, that Summer “Full Moons” are always very low on the horizon, while Winter “Full Moons” can be very high overhead.

Here’s a table of the altitude of the “Full Moon” when due south. Remember the times in this table don’t match the exact time of the Full Moon, but instead have been chosen as the closest in time to that instant, and so have be labelled “Full Moon” (in quotes).

| Month | Date of Full Moon |

Time of Full Moon (UT) |

Time/Date of “Full Moon” due S |

Time from/since instant of Full Moon |

Altitude due S (degrees)** |

| June 2011 | 15 June | 2014* | 0127BST 16 June 2011 | +4h13m | 10° 05′ |

| July 2011 | 15 July | 0640* | 0012BST 15 July 2011 | -7h28m | 10° 24′ |

| August 2011 | 13 August | 1857* | 0126BST 14 August 2011 | +5h27m | 19° 19′ |

| September 2011 | 12 September | 0927* | 0049BST 12 September 2011 | -9h38m | 31° 49′ |

| October 2011 | 12 October | 0206* | 0053BST 12 October 2011 | -1h13m | 44° 16′ |

| November 2011 | 10 November | 2016 | 0005GMT 11 November 2011 | -3h49m | 53° 24′ |

| December 2011 | 10 December | 1436 | 0030GMT 11 December 2011 | +9h54m | 56° 03′ |

| January 2012 | 09 January | 0730 | 0006GMT 09 January 2012 | -7h24m | 53° 36′ |

| February 2012 | 07 February | 2154 | 0031GMT 08 February 2012 | +2h37m | 43° 47′ |

| March 2012 | 08 March | 0939 | 0000GMT 08 March 2012 | -9h39m | 35° 37′ |

| April 2012 | 06 April | 1919* | 0145BST 07 April 2012 | +5h26m | 21° 45′ |

| May 2012 | 06 May | 0335* | 0102BST 06 May 2012 | -3h33m | 15° 20′ |

| June 2012 | 04 June | 1112* | 0047BST 04 June 2012 | -11h25m | 11° 49′ |

* UK observers should add on one hour for BST

** The altitude here is based on my observing location in Glasgow, Scotland. You can find out how to work out how high these altitudes are here.

As you can see from this table, the highest “Full Moon” due S this year occurs at 0030 on 11 December 2011, when the Moon will be over 56° above the southern horizon (approximately the height of the midsummer mid-day Sun which culminates at 57°34′).

Compare this to the “Full Moon” this month, just after the eclipse, in the morning of 16 June, when the Moon barely grazes 10° above the horizon, and you can see just how low the midsummer Full Moon can be.

In fact the closeness of summer “Full Moons” to the horizon means that this is an ideal time of year to try and observe the Moon Illusion.

UPDATE: Here’s a very cool speeded up video of the Moon cycling through its phases, as see by the LRO spacecraft: